2024 2.21

Digital / Casette

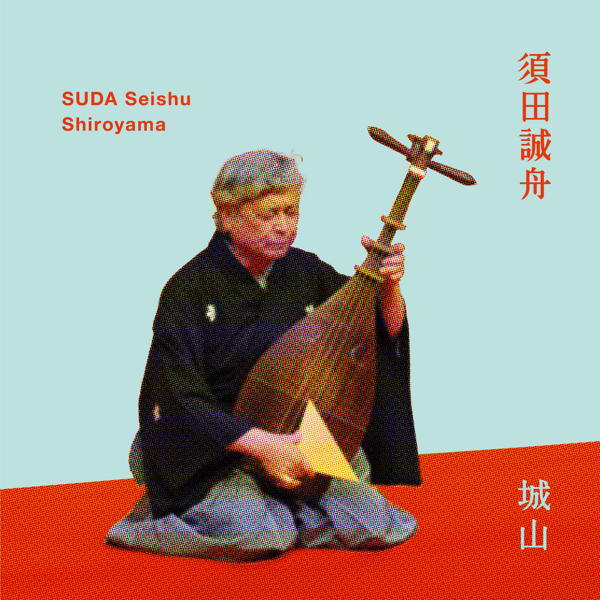

Biwa & Voice: SUDA Seishu

Recording: Masaoki Moroishi

Mastering: Taku Unami

Curation and text: Hyotan Namaz

Cover design: Graphic Potato

Coordination & Release: ato.archives

This tape is a part of the series titled “Kawanosayo / 川の作用”

ata 011

About the Song “Shiroyama”

“Shiroyama” is one of the most famous songs in the Satsuma-biwa repertoire. It tells the story of the final moments of Saigō Takamori, a hero of the Meiji Restoration and a symbol of Satsuma’s samurai spirit.

After playing a central role in the Meiji Restoration, Saigō became a key figure in the new government. However, political disagreements forced him to retire to his hometown of Kagoshima. During this time, Japan’s rapid modernization under the Meiji government caused dissatisfaction among the samurai class, who had once held power. Frustration grew, and rebellions broke out across the country.

In 1877, the Satsuma Rebellion began, led by young samurai in Kagoshima. Reluctantly, Saigō was persuaded to lead the uprising as its general. This rebellion, known as the Satsuma Rebellion or the Seinan War, was ultimately crushed by the modernized government forces. Cornered at Shiroyama, a hill in central Kagoshima that remains a city landmark, Saigō met his end, taking his own life to preserve his honor.

The story of “Shiroyama” as a biwa song originates with Katsu Kaishū, another key figure of the Meiji Restoration who famously negotiated the peaceful surrender of Edo Castle. Katsu was a close friend of Saigō and deeply admired his character and leadership. Years after the Satsuma Rebellion, Katsu attended a performance by Nishi kōkichi, a master of Satsuma-biwa. Moved by the music, Katsu shared his respect for Saigō and asked Nishi to create a biwa song about Saigō’s last stand, preserving his legacy through music.

Though eager, Katsu struggled to write the lyrics, overwhelmed by his deep emotions for his late friend. After three years of effort, he finally completed the poem in 1885. Nishi composed the music within a week and debuted it in Katsu’s presence. Overcome with emotion, Katsu reportedly wept and said, “I didn’t create this song to make people cry, yet I cannot stop my tears.”

“Shiroyama” became Nishi’s signature piece and has since been passed down as an iconic masterpiece of Satsuma-biwa music.

Despite its relatively short length for a biwa song, “Shiroyama” incorporates many key elements of the Satsuma-biwa tradition:

Kuzure: A tremolo technique used to create vivid battle scenes.

Shigin: The recitation of Chinese-style poetry with dramatic intensity.

Gingawari: A sorrowful style of singing used to convey deep emotion.

With its elegant poetry and masterful musical structure, “Shiroyama” is widely regarded as a high point of the Satsuma-biwa tradition and a perfect introduction to its rich history.

【解説】

「城山」は明治維新の中心人物の一人で薩摩の英雄、西郷隆盛の最期の場面を描いた歌であり、薩摩琵琶を代表する曲目といってよい。西郷隆盛は、明治維新後、新政府で要職についたが、政治的な意見対立に敗れ、故郷鹿児島で隠遁生活を送っていた。折しも、維新政府が国家を急速に近代化を進める中で、前時代の支配階級であり、維新の担い手ともなった武士階級が煽りを受け不満が蓄積、各地で反乱が相次ぐ状況になってきた。こうした状況下、明治10年(1877年)鹿児島でも若い士族を中心に反乱が勃発。西郷隆盛は彼らに推される形で、反乱軍の総大将となった。この戦いが西南戦争である。しかし近代化した新政府軍を前に薩摩の反乱軍は敗れ、追い詰められた西郷は、鹿児島市内の中心部、鹿児島の街のシンボルである城山において、自刃するに至った。

この有名なエピソードを琵琶歌としたのは、同じく明治維新期の大物で、江戸城無血開城に貢献のあった勝海舟である。勝は西郷と肝胆合い照らす友人であり、その人柄、能力を高く評価していた。西南戦争から過ぎる事数年、名人西幸吉の薩摩琵琶の演奏を聞きいたく感動した勝は、西郷の偉大さを語った後、その場で、西郷の城山陥落の歌を作ってみたいから、それを西の琵琶で永久に残して欲しい、と依頼。といったものの、西郷への思いが強すぎたのか、勝は歌の歌詞がなかなか書けず、苦労したのちに約3年後の明治18年、漸く完成。これに、西が一週間ほどで作譜して、勝らの前で初弾奏の運びとなった。これを聴いた勝は涙を抑えられなくなり、「泣く為に作歌したわけではないのに涙が出るのをどうしようもない」と語ったという。

「城山」は西の代表曲となり、同時に薩摩琵琶のアイコンとして現在に至るまで歌い継がれている。

「城山」は琵琶歌としては比較的コンパクトな長さにも係わらず、トレモロ奏法を多用し主に合戦など臨場感のあるシーンを表現するのに使われる「崩(くずれ)」、漢詩を歌い上げる「詩吟」、哀切なシーンを表現するのに使われる「吟替り(ぎんがわり)」といった、薩摩琵琶歌の主要な要素を一通り含んでおり、詩句の格調高さのみならず、琵琶歌としての構成の上でも完成度が高く、まさに薩摩琵琶の名曲というに相応しい。

About the Song “Sumie”

“Sumie” is believed to have been written by Suwa Kanetoshi (1590–1667), a retainer of Shimazu Mitsuhisa, the 19th head of the Shimazu clan. Suwa was not only a respected samurai but also a highly regarded poet. This makes “Sumie” a song with a history spanning over 300 years.

According to Chida Yukio, a scholar of classical Japanese literature and the author of Annotated: Collection of Satsuma Biwa Songs, “Sumie” has long been revered as the king of Hauta songs in the Satsuma-biwa repertoire. Hauta songs are shorter pieces compared to the narrative epics called danmono, which recount tales of battles and historical events. In Chida’s classification, “Sumie” falls under the category of Buddhist songs within the Haura tradition. Its lyrics reflect on the impermanence of worldly life, extol the virtues of Buddhist teachings, and encourage devotion to the Buddhist path.

Many of the classic Hauta songs passed down from the Edo period focus on religious or moral themes, often inspired by Buddhism or Confucianism. This aligns with the origins of Satsuma-biwa as an art form designed by Shimazu Tadayoshi, a lord of the Shimazu clan, to cultivate the minds and morals of samurai.

The lyrics of “Sumie” include many Buddhist terms, making them less immediately accessible. However, through repeated performance and listening, the song’s depth and emotional resonance gradually sink into the heart. This profound quality justifies its reputation as the “king of Hauta.”

The title “Sumie” (meaning “ink painting”) is derived from the opening lines of the song, a poetic verse:

“What is the heart? How can one explain its mystery?

The sound of the wind through pines, painted in ink.”

Though “Sumie” is considered one of the most important works in the traditional Satsuma-biwa repertoire, it is rarely recorded and difficult to find in modern collections. This recording is thus a rare and valuable opportunity to experience this timeless masterpiece.

【解説】

「墨絵」は島津家19代当主の島津光久(1616-1695)の家老であり、歌人としての評価も高かった諏訪兼利の作と言われているから、300年以上前の作品ということになる。古来、端歌の王と称されて弾奏曲目中で最も尊重されてきたと、国文学者で『註解:薩摩琵琶歌集』の著者である千田幸夫は述べている。端歌とは、短編の琵琶歌のことで、他に軍記物などを中心とした長編の叙事詩では段物と呼ばれる。千田の分類によると、「墨絵」は端歌の中でも釈教の歌に位置付けられる仏教歌で、世間無常を説き、仏法の功徳を述べて仏道への帰依をすすめる内容となっている。江戸時代から伝わり端歌の名曲とされる曲には、仏教や儒教など教えをベースとした宗教的、教訓的な内容のものが多くなっているが、これは、武将の島津忠良が、武士の情操教育として薩摩琵琶を創始したという、薩摩琵琶の誕生の伝承から考えれば頷けることである。この「墨絵」も仏語が多用され、一読して分かりやすい内容ではないが、繰り返し歌う事でしみじみと心に染み込む奥行きがあり、端歌の王と言われるのに相応しい深さがある。

曲名の「墨絵」は冒頭の道歌、「心とは 何を云うらむ不思議さよ 墨絵に書きし松風の音」から取られている。

上述の通り、伝統的な薩摩琵琶においては非常に重要な曲目であるが、現在手に入りやすい音源で「墨絵」が収録されているものは殆どなく、貴重な録音である。

解説/Text: Hyotan Namaz

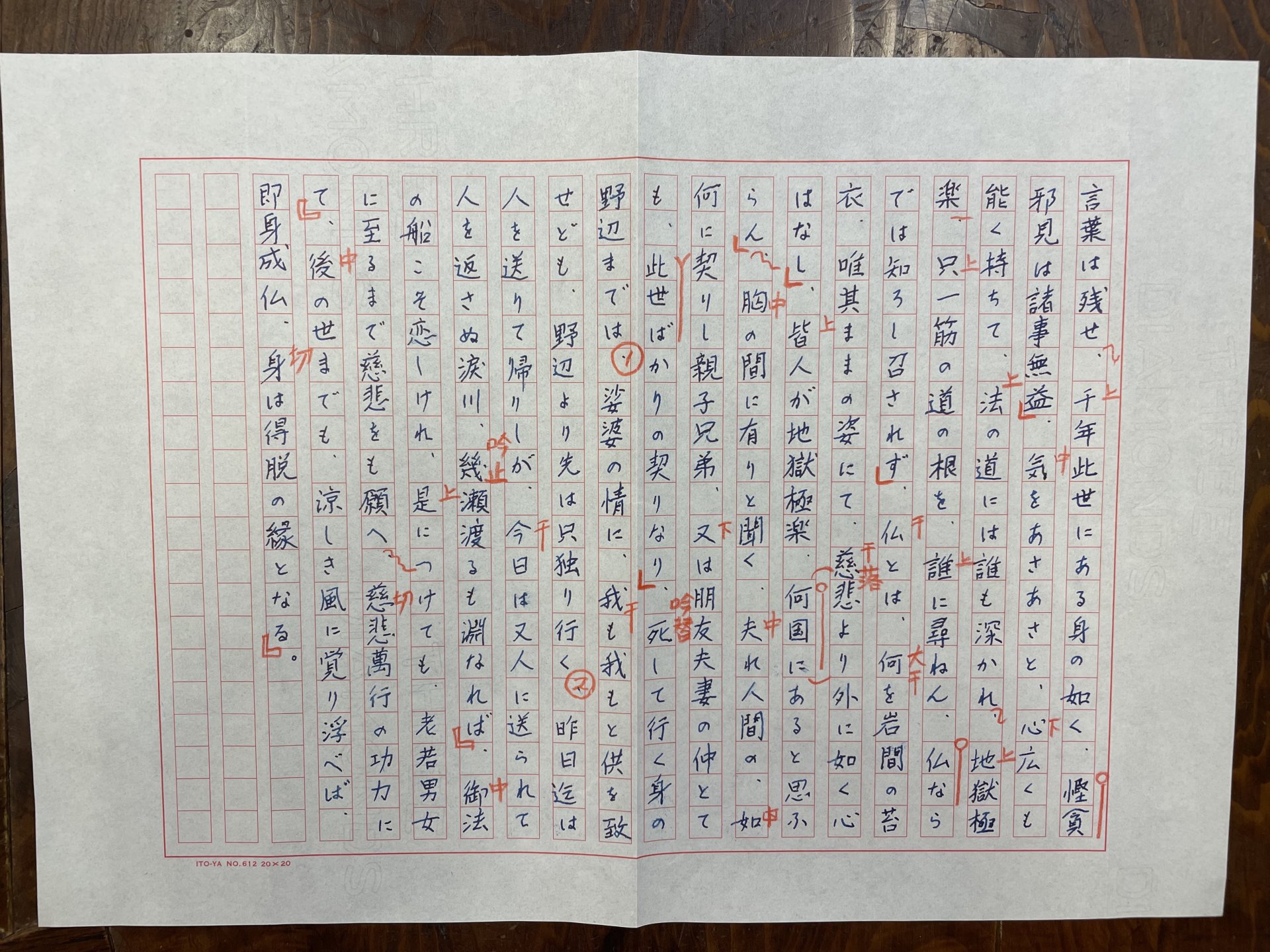

それ達人は大観す 抜山蓋世の雄あるも 栄枯は夢か幻か 大隈山の狩倉に 真如の月の影清く 無念無双を観ずらむ 何を怒るやいかり猪の 俄かに激する数千騎 勇みに勇むはやり雄の 騎虎の勢い一徹に とどまり難きぞ是非もなき 只身一つを打ち捨てて、若殿原に報いなん 明治十年の秋の末 諸手の戦打ち破れ 討ちつ討たれつやがて散る 霜の紅葉の紅の 血潮に染めど顧みぬ 薩摩武夫の雄叫びに 打ち散る弾丸は板屋打つ 霰たばしる如くにて 面を向けん方ぞなき こだまに響く鯨波の声 百の雷ひと時に 落つるが如き有様を 隆盛打ち見てほくそ笑み あな勇ましの人々やな 亥の年以来養いし 腕の力も試し見て 心に残ることもなし いざ諸共に塵の世を 遁れ出でむはこの時と 唯一言を名残にて 桐野村田を始めとし 宗徒の輩諸共に 煙と消えし丈夫の 心の内こそ勇しけれ

孤軍奮闘破囲還(孤軍奮闘 囲を破って還る)

一百里程塁壁間(一百の里程塁壁の間)

我剣已折我馬斃(我が剣は已に折れ 我が馬は斃る)

秋風埋骨故郷山(秋風 骨を埋む故郷の山)

官軍これを望み見て 昨日までは陸軍大将と仰がれ 君の寵遇世のおぼえ 類なかりし英雄も 今日は敢えなく岩崎の 山下露と消え果てて 移れば変わる世の中の 無常を深く感じつつ 無量の思い胸に満ち ただ蕭然と隊伍をととのへ 目と目を見合わすばかりなり 折しもあれや吹き下ろす 城山松の夕嵐

岩間に咽ぶ谷水の 非情の声もなんとなく 悲鳴するかと聞きなされ 戎衣の袖をいかに濡らすらん

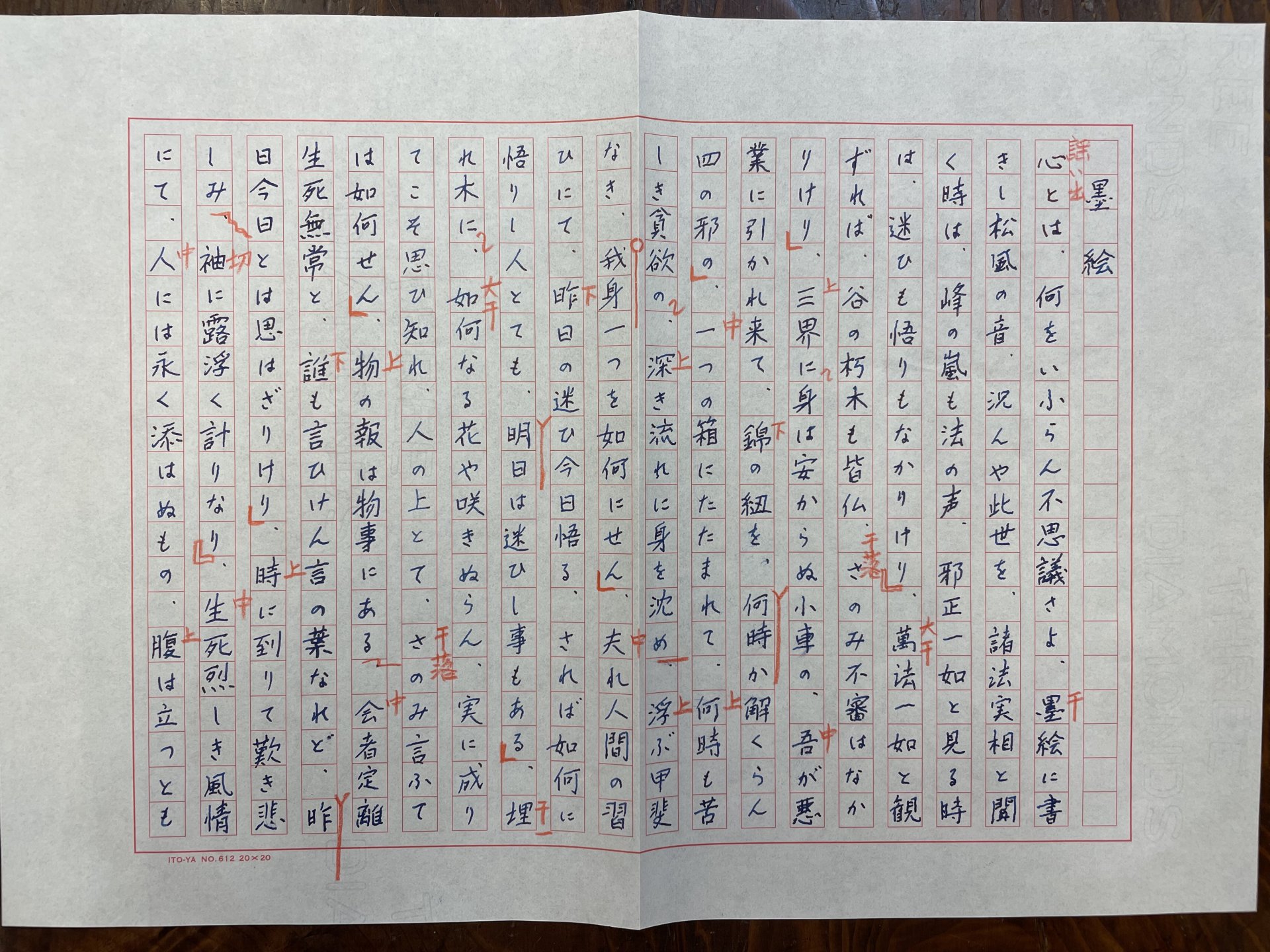

心とは 何を云うらむ不思議さよ 墨絵に書きし松風の音 況んや此世を 諸法実相と聞く時は 峰の嵐も法の声 邪正一如と見る時は 迷いも悟りもなかりけり

萬法一如と観ずれば 谷の朽木も皆仏 さのみ不信はなかりけり 三界に身は安からぬ小車の 吾が悪業に引かれ来て 錦の紐を何時か解くらむ四つの邪の 一つの箱にたたまれて 何時も苦しき貪欲の 深き流れに身を沈め 浮かぶ甲斐なき 我が身一つを如何せん それ人間の習いにて 昨日の迷い今日悟る されば如何に悟りし人とても明日は迷いし事もある 埋もれ木に如何なる花や咲きぬらむ 身になりてこそ思い知れ 人の上とて さのみ言うては如何せん 物の報いは物事にある 会者定離生死無常と 誰も言ひけん言の葉なれど 昨日今日とは思わざりけり 時に到て嘆き悲しみ 袖に露浮く計りなり

生死烈しき風情にて 人には永く添わぬもの 腹は立つとも言葉は残せ 千年此世にある身の如く 慳貪邪見は諸事無益 気をあさあさと 心広くも能く持ちて 法の道には誰も深かれ 地獄極楽 ただ一筋の道の根を 誰に尋ねん 仏ならでは知ろし召されず 仏とは 何を岩間の苔衣 唯其儘の姿にて 慈悲より他に如く心はなし 皆人が地獄極楽 何国にあると思ふらむ 胸の間に有りと聞く 夫れ人間の 如何に契りし親子兄弟 又は朋友夫妻の仲とても 此世計りの契りなり 死して行く身の野辺迄は 娑婆の情けに 我も我もと供を致せども 野辺より先は只独り行く 昨日までは人を送りて帰りしが 今日は又人に送られて 人を返さぬ涙川 幾瀬渡るも淵なれば 御法の船こそ恋しけれ 是につけても 老若男女に至るまで慈悲をも願へ 慈悲萬行の功力にて 後の世までも涼しき風に悟り浮かべば 即身成仏 身は得脱の縁となる

SUDA Seishu

SUDA Seishu is a Satsuma-biwa and Heike-biwa performer from Tokyo, Japan. He began studying Satsuma-biwa under Tsuji Seigo in 1968 and won first prize at the Japan Biwa Music Competition in 1970. SUDA has inherited the Myojufu and Tennamufu playing techniques, passed down from legendary biwa masters of the late Edo and Meiji periods. As one of the leading performers of the traditional Seiha (Orthodox School) style of Satsuma-biwa, he has been active for many years, preserving its rich cultural heritage.

In 1991, SUDA began studying Heike-biwa (Heikyoku) under Kindaichi Haruhiko and has since performed extensively as a Heikyoku artist.

He regularly performs at prestigious events such as the Traditional Japanese Music Appreciation Concert hosted by the National Theatre of Japan and the Biwa Music Master’s Recital organized by the Japan Biwa Music Association. In addition to solo performances, he actively collaborates across artistic disciplines, including theater productions and annual performances of ‘The World of Tale of the Heike’ featuring Noh, Kyogen, and Heikyok since 1998.

SUDA has also performed internationally in countries such as Germany and Portugal as a cultural ambassador, contributing to global cultural exchange through the art of the biwa.

He currently serves as the President of the Japan Biwa Music Association and the President of the Satsuma Biwa Seigenkai.

須田誠舟

東京都出身の薩摩琵琶・平家琵琶奏者。1968年より辻靖剛に師事し薩摩琵琶の指導を受ける。1970年、「日本琵琶楽コンクール」で優勝。幕末・明治期に活躍した伝説的な琵琶の名手の流れを汲む、妙寿風・天南風の弾法を受け継ぎ、薩摩琵琶の伝統的なスタイルである薩摩琵琶正派の代表的な演奏家として長く活躍している。1991年からは金田一春彦に師事して平家琵琶(平曲)を学び、平曲の演奏家としても活動。

国立劇場主催「邦楽鑑賞会」、日本琵琶楽協会主催「琵琶楽名流会」などで定例的に演奏するのに加え、演劇への参加や、能・狂言・平曲による「平家物語の世界」に1998年より毎年出演するなど、他分野とのコラボレーションにも積極的に取り組む。

文化交流使節としてドイツ、ポルトガル等で琵琶を演奏するなど、海外公演多数。

日本琵琶楽協会会長。薩摩琵琶正絃会会長。